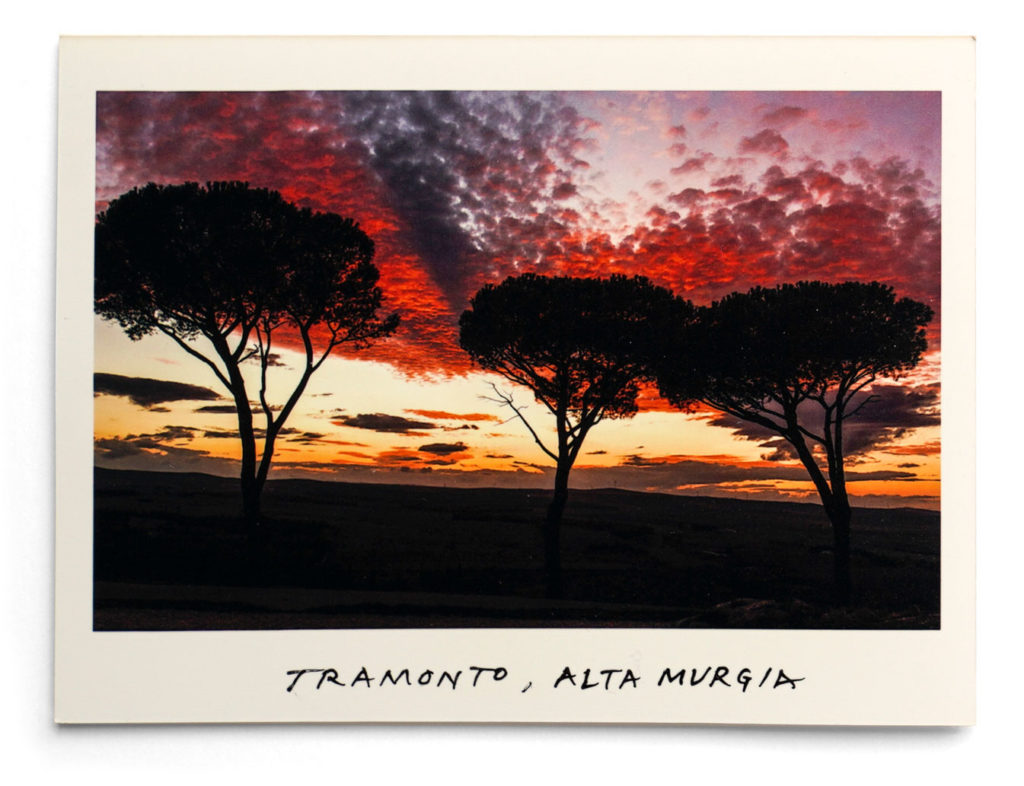

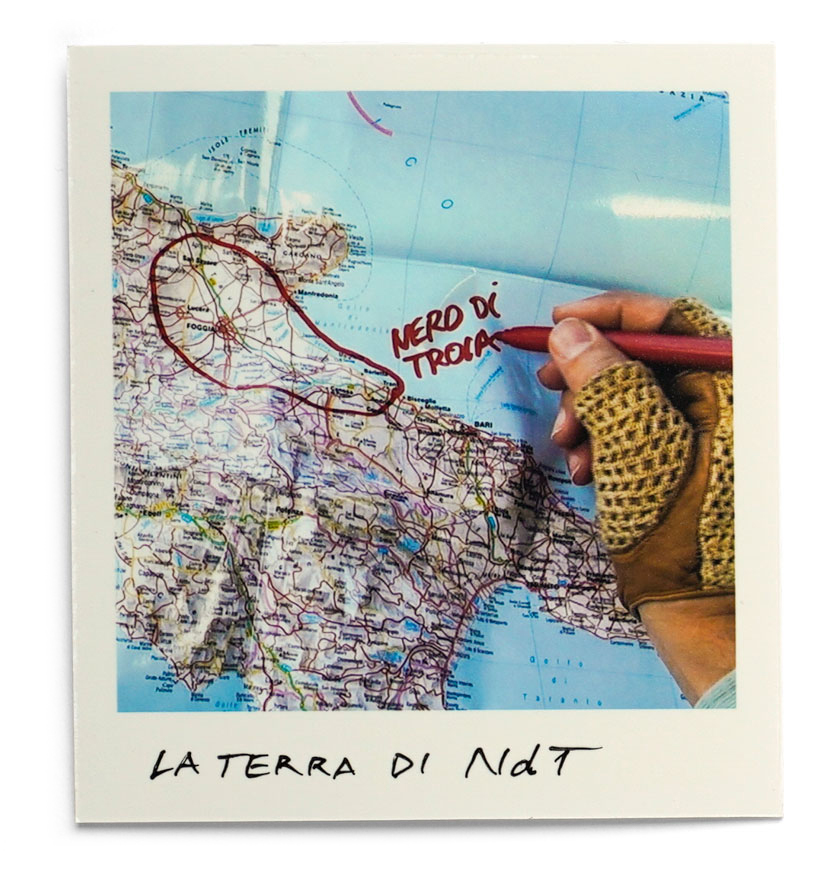

A road trip in a vintage Lancia Zagato in northern Puglia to discover the wine-making grape Nero di Troia. Our protector and guide is the one and only (the spirit of) Federico II.

e weren’t prepared for the magnitude of this legendary man, the master multi-tasker.

An avid astronomer, an innovative agricultural manager, a compassionate politician, a science advocate, an architect, a writer, an experienced falconer. He was also the king of Sicily, the king of Jerusalem, the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, the Duke of Sweden. He had 13 children with 7 wives and 6 children with 6 other women… and he loved to drink the “full-bodied wine from Troia”.

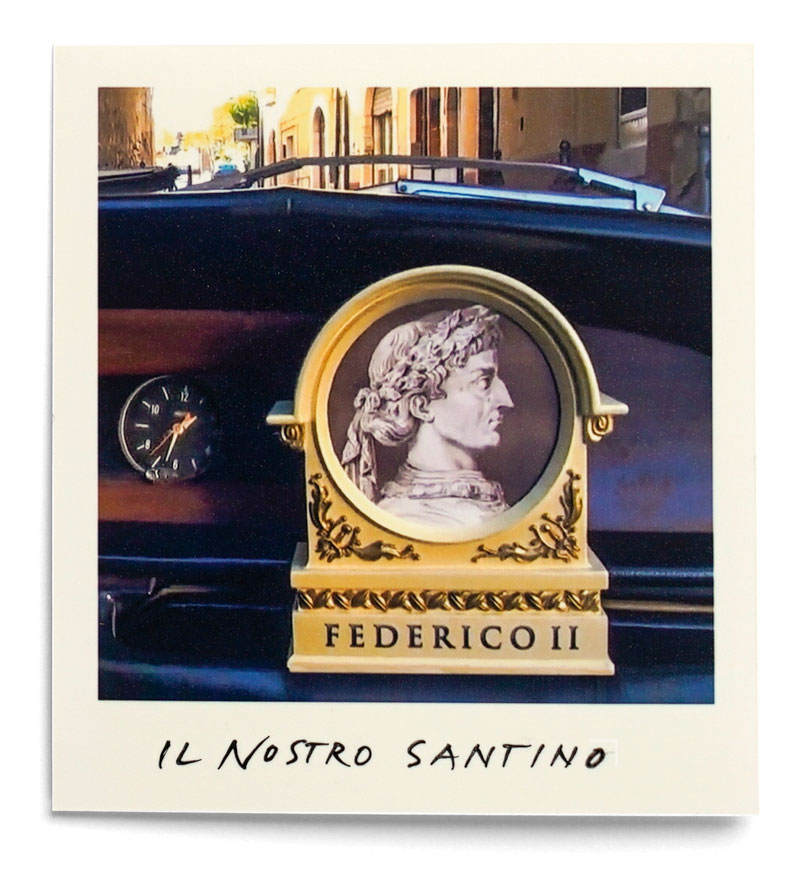

After almost 800 years the spirit of Federico II still permeates this land of Puglia, nestled in the “heel of Italy’s boot”. Seems like everyone we met spoke about the Stupor Mundi, (Mr. Wonder of the World) his local nickname, as if he still lives around the corner. Today, he’s an ancient celebrity influencer in this arid land of sun, sea and wind-powered energy. We’re here on a journey to discover Federico II’s preferred wine, Nero di Troia.

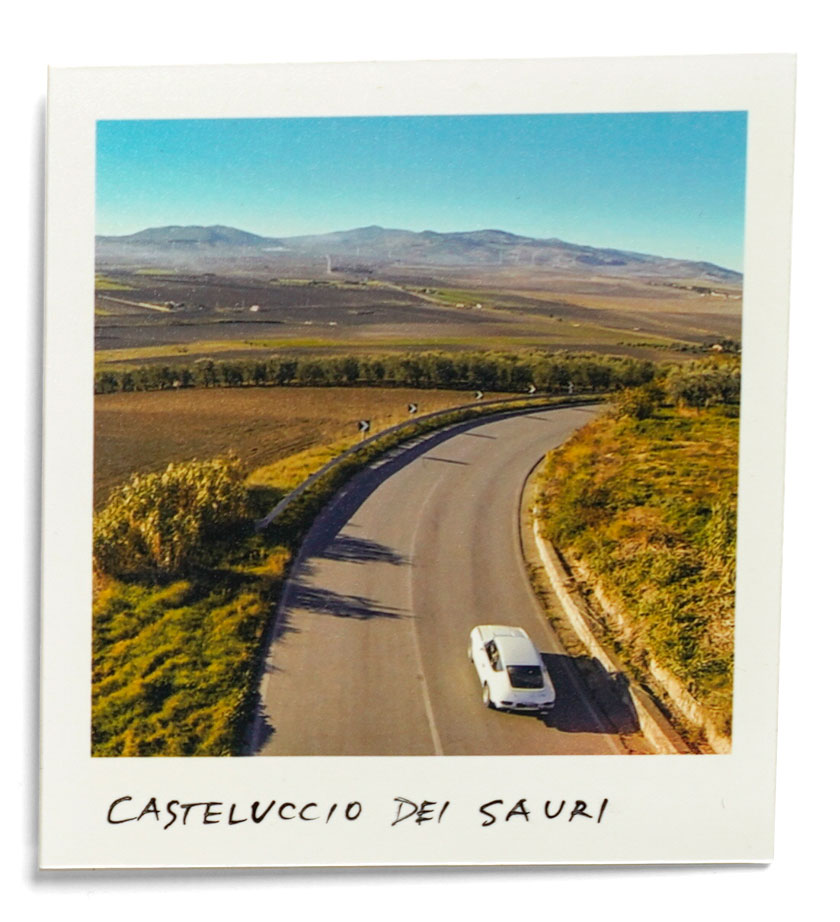

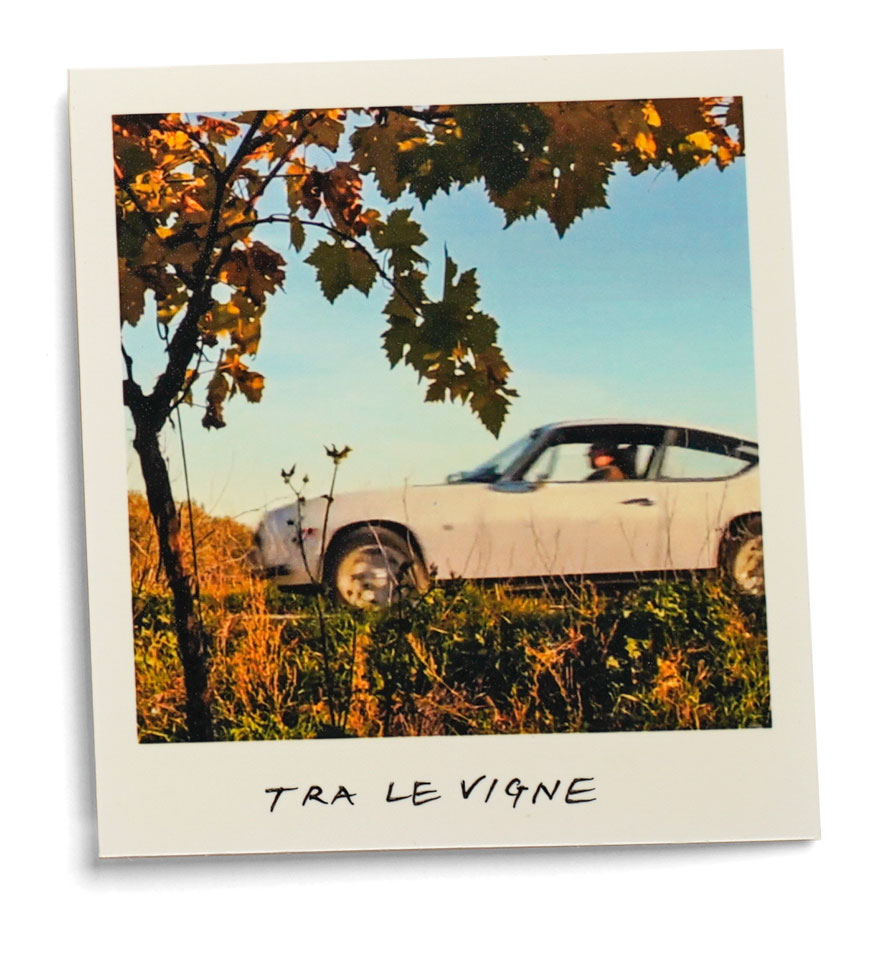

We climb into our rented white vintage 1971 Lancia Zagato, roll down the windows and zip through the small country roads in the Alta Murgia just a few kilometers from the coastal town of Barletta. The warm breezes of finocchietto, and wild sage fill our hair and lungs. The smell of a profound Greek-Albanian history is in the air.

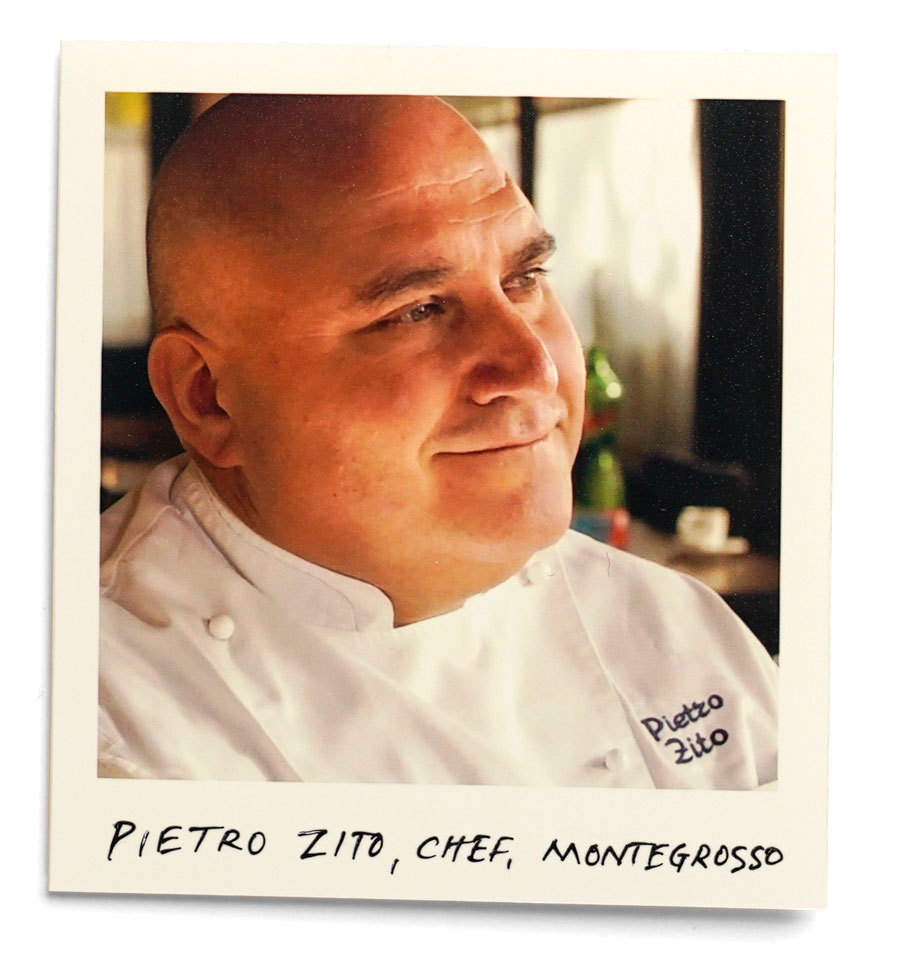

Our first stop is Montegrosso, a sleepy village in the Murgia country-side. We meet Pietro Zito, the renown “kilometer zero” chef and expert forager, at his restaurant Antichi Sapori. “Coming to Puglia is like visiting a hundred different places with a hundred different realities. Less than 20km from the sea, we’re here in the Alta Murgia, a totally different landscape with totally different foods.” He told us a story: “Federico II once had two chefs who served him, one German and one from Puglia. It’s well known that Federico preferred Pugliese cuisine. At the moment just before the Pugliese chef died, the German chef asked him, ‘why are your dishes so much better than mine?’ ‘Extra virgin olive oil.’ were his last words. He always used the local olive oil in his dishes. And he always served the wine from his land, Nero di Troia, which we still drink today. It’s a sincere, honest wine.”

Less than 20 km from the wild vegetable gardens of Pietro, in the heart of the Murgia national park, we can see in the distance on a rocky peak the imposing Castel del Monte. A masterpiece by Federico II, now a World Heritage Site by UNESCO It dominates this landscape. It’s a harmonious medley of classical, medieval, oriental Islamic and northern European Cistercian Gothic elements. Elegantly austere, the castle’s design, based on the number eight, creates symmetries of light during the winter solstice and the summer equinox.

Its design based on mathematical and astronomical rigor is imbued with symbolism and has been a magnate for scholars throughout the centuries. With eight octagonal towers, eight trapezoidal rooms on the ground floor and eight on the first floor, all are positioned to form more octagons. It’s believed that the open courtyard of the castle once had an octagonal pool. Imagine how it must have been to float on your back while studying the night skies.

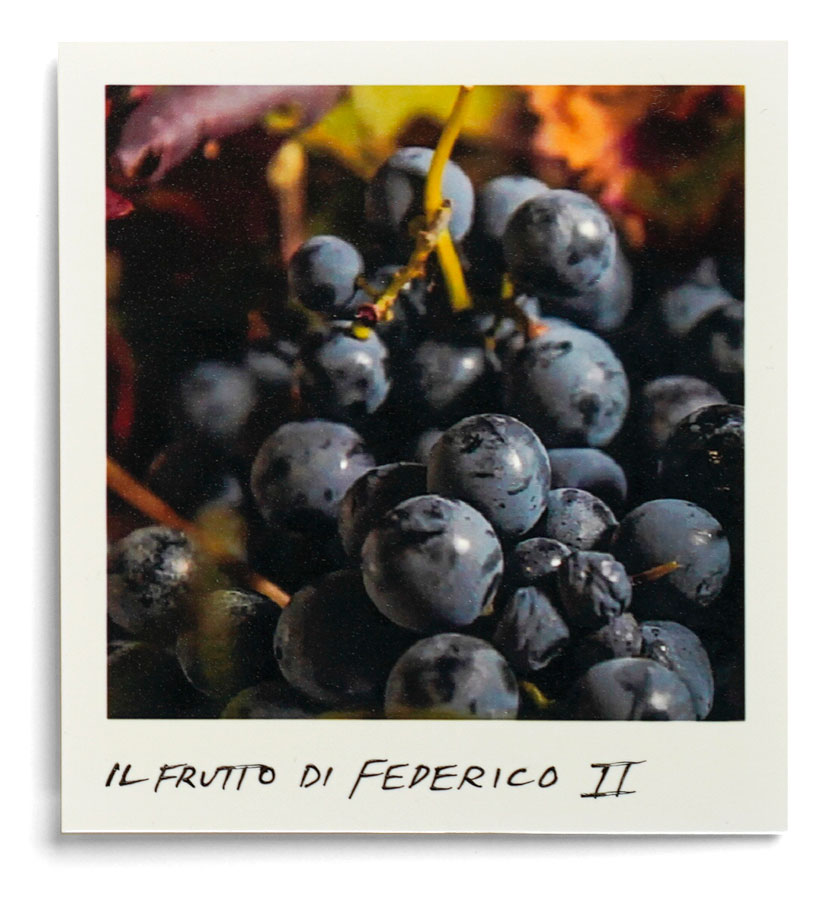

We’re back on the road heading to the coastal town Trani to meet Cristoforo Pastore, an enologist for several winemakers in the area. We sit at a bar overlooking the Adriatic Sea and he pours us a glass of Nero di Troia. Between sips he tells us there are two schools of thought on where the name comes from; one is that it’s from the ancient Greek city in Asia Minor and the other is that it’s a deformation of the name Croia (or Krujë), the old capital of Albania. Ties between Puglia and Albania was very strong in early roman times, and through the exchange of goods, men and culture, surely some Troia vines found there way over.

A perfumed aroma wafts from my glass of wild succulents and herbs, just like those breezes from our drive through the arid country-side. A burst of red fruit fills my mouth with just a pinch of black pepper. I’m taking in a multi-sensory liquid that speaks of this Pugliese land.

Cristoforo continued: “Federico II cultivated his wine near the village of Troia, known for its Romanesque cathedral with a spectacular facade and rose window. He went on talking about the virtues of Nero di Troia wine and its grape which contains a significant level of resveratrol, a strong antioxidant and apparently a strong anti-cancer agent. “I always remember the old local people talking about Nero di Troia for its healthy elixir qualities. They say those who drink Nero di Troia will live to be 100 years old”.

The average life span during the year 1200 was about 35 years according to most studies. Frederick II lived until he was 56 years old. That’s 60% longer than most. Must we ask ourselves why?

20 Mondi meets Enrico Togni, an independent winemaker in northern Italy, Val Camonica, guardian and evangelist of the rare autochthonous grape Erbanno.

teaming, savory aromas invite us to sit down at Cinzia’s kitchen table.

Dishes of braised rabbit, mountain polenta, and stewed cabbage and potatoes from their garden cover the table. I’m in heady comfort food ecstasy when the man sitting in front of me, brings me back to reality. He tells me that he himself slaughtered the rabbit this morning.

I immediately understand this is a guy who gets things done.

Enrico Togni, Cinzia’s partner, is an authentic Camuno. Born and raised here in the Camonica Valley in northern Lombardia, just 20 km from the Swiss border, his family has been working this land for over 4 generations. He’s 38 years old with disheveled hair, and, as he helps himself to his rabbit, he tells us in an emotional voice of when he started working the 70 yr old vineyards inherited from his grandfather.

He recalls one of the first things he and his mother noticed when they took over the vineyard: the grapes were not all the same.

They proceeded to make a detailed map of the vineyard rows. “Yes, there were the usual suspects: Nebbiolo, Barbera and Marzemino. But there remained a mysterious plant, a varietal we had never seen before. We took a cutting to the respected San Michele dall’Adige Agricultural Institute and the DNA tests showed it was a rare specimen of an herbaceous, autochthonous red grape variety called locally called Erbanno”, after a small town at the foot of nearby Mount Altissimo where it has been cultivated for generations.

Enrico pours us a glass of Erbanno, but not the classic version, instead a rosè, vinificato in rosato. It’s fresh tasting, pleasant, and surprisingly structured. It holds up well, complementing our flavorful dishes.

A few months after the DNA discovery, the grape was entered in the Italian National Register of Vine Varieties. It was 2003, and on that day Enrico left law school to dedicate himself to the land.

Over time, Enrico got to know this grape from root to fruit. A late ripening vine, he learned of its resistance to harsh climatic conditions and diseases. “Tough as rock” he claims, perfectly suited to to his natural and organic cultivation style.

Enrico goes on talking about the characteristics of grapes, “like any living being, they are profoundly formed by climate, soil and by human intervention. With time, these three elements transform the grapes into wine. It’s a concept that the French have condensed into one word: terroir.

“A sheep from Bergamo is different from a sheep in Sardinia, despite both being sheep. The grass they eat is different. The water they drink contains different minerals. So even if they’ve discovered that the Erbanno is genetically equal to the varietal found near Bologna, called Lambrusco Maestri, Erbanno has evolved over time, and developed unique characteristics thanks to our unique terroir.”

Today Enrico cultivates 3 hectares of vineyards, 2 of which are Erbanno. They’re certified organic, and biodynamic by nature (no official biodynamic certificate). He can produces a total of twelve thousand bottles in a good year. Enrico recently gave away some of his Erbanno vines to local wine producing friends who are starting new vineyards. He wants the awareness of Erbanno to grow and is curious to share it and see how other producers interpret it.

By encouraging collective efforts, what today is a rarity, tomorrow could become an icon of Val Camonica.

I’m finishing my braised rabbit and Cinzia lays a plate filled with a medley of Camuno cheeses. Mountain grasses and herbs are sensed in these milky cheeses, aged high at high altitude pastures for up to ten years. Silter Dop is the star cheese on the plate and is prized all over Italy.

Enrico opens a bottle of Erbanno, this time red, a 2014 vintage.

I am astounded by its deep, dark, blackberry color, close to a Pantone 518C. It fills my mouth with mountain freshness.

A strong, wild, impulsive character with the minerality of the local rock from this glacial valley, Europe’s widest, used since prehistorical times to cross the Alps. This valley is rich in biodiversity with indigenous plants, some now almost extinct, with other autochthonous grapes like Valcamonec and Sebina.

Another local winemaker Alex Bellingheri, who owns Agricola Vallecamonica, is currently recovering Ciass Negher, another local, almost extinct red grape.

At the end of our lunch Cinzia confides in us her concerns: “In no way is it easy to be a wine maker here. We work so hard for an entire year. Then, all it takes are ten minutes of hail and we won’t bring anything home”. But Enrico and Cinzia have a solution: they have in the works a diversification plan. Next year they will be raising sheep, producing honey, cultivating vegetables, and fermenting beer.

And of course they’ll be making Erbanno wine. It’s an enduring bond with their mountain land.

The New York waiter said “It’s an Italian Champagne!” That’s exactly what the next generation of Franciacorta producers don’t want to hear.

And they’re trying to change it.

ordered my first bottle of Franciacorta about 2 y5ears ago, in a small restaurant in the West Village in New York. I was unfamiliar with the name at the time, so the waiter explained: “It’s like Champagne… an Italian Champagne!” I was a bit hesitant at first, but, after my first sip, I was pleasantly surprised.

Last week I visited a few producers in the wine zone Franciacorta, in the northern region of Lombardia, a pastoral countryside between the blue waters of Lake Iseo and the city of Brescia. All of the producers I met expressed the same sentiment: “…oh, we’re still dealing with the perception that we make Italian Champagne. It’s exactly what we don’t want to hear. Franciacorta must be known as Franciacorta!”

The reason for my trip was to find out what the next generation, the daughters and sons of winemaking families in Franciacorta, are doing to confront this piggy-back comparison, and how they are dealing with being given the responsibility to lead their family businesses into an unpredictable future.

The land of Franciacorta is one of three wine domains in Europe, unique in Italy, that esclusively produces wine with the metodo classico, or méthode champenoise. (Champagne and Cava are the others.) Nestled in a glacier-created amphitheater with Lake Iseo as the stage, breezes from the farmlands mix with the winds coming off the lower alps and that then skim off the lake. Its ideal microclimate produces 15 million bottles a year of the high-end Italian bubbly. Franciacorta became a DOC in 1967 and in 1995 was upgraded to a DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita), the first in Italy, and who’s name, like Champagne, refers to three things: territory, production method and the exclusive name of the wine.

My first stop, about a mile outside the small town of Erbusco, I met the Giulia Cavalleri and her daughter Diletta. In a large room of high ceilings with elegant dark wood beams and huge imposing canvases from 1500 on the walls, they greeted me with an air of winemakers in their blood, a sense of self-assurance from the many like-minded generations before them. “We have documents from the year 1450 citing our family’s cultivated land in Erbusco, and we’ve been here ever since”. Giulia’s father was one of the founders of the Franciacorta Consortium created 26 years ago together with 12 producers and he served as it’s first president. The consortium now consists of 120 aziende, contributing to the recent rise of wealth in the area which historically lacked the fertile soils needed by cash crops at the time: grains, fruits and vegetables. The industry was slow to develop, and, unlike richer areas in of post war Italy, this countryside remained pristine.

Diletta looks much younger than her 32 years. She studied business at Bocconi University in Milan and is currently managing the administration, marketing and communications aspects of the azienda familiare, the family business, the Cavalleri winery. Her brother, Francesco, 33, studied engineering at the same school and now manages the vineyards and general production. But there was a time when neither of them thought they’d end up working here. Their parents never pushed them, instead they encouraged them to get out and see the world, giving them space to decide their own personal paths. Diletta went to London for a year and a half to study art history and became economically self sufficient with a job working for the fashion company Max Mara. Francesco worked as a scuba diving instructor in the Maldives. “But I guess it was a natural attraction of having wine making in our blood that lured us back to Erbusco.” said Diletta.

Overseeing the sales aspect, Diletta uses social networks sparingly, not feeling that constant pressure to always post new content. “We mostly use it for family and friends, not as an indispensable marketing tool. This works for us by keeping our messages authentic; we focus on the real things we do.”

A challenge Diletta faces today is how to elevate awareness of quality of Franciacorta without comparing it to Champagne. “Wine is a descendant of the land. Our wines are not like Champagne because here the Chardonnay grape expresses itself very differently. The climate and soils are different. Franciacorta is fresher, more floral. We have a unique maturation period thanks to our Mediterranean micro-climate.”

Another challenge, she says, is that it’s not easy being a woman in the wine business. “Our company has 70 sales agents and they’re all men.” Her mother Giulia joined in, “It was easier for me 27 years ago. I was the first woman to work in my family. There was a new energy after 1968 cultural revolution. The possibilities seemed more open then. But for the last 15 years it has become more difficult for women. In the world of wine, Italy is very macho. It’s a cultural problem and it needs to be resolved because women can bring so many positive things to the world of wine. We are better at multi-tasking which makes us very good managers. Women have an excellent nose, we have it inside our DNA to recognize our children, to sense when food is ready or if it’s safe to eat; we have a better appreciation of perfumes. Diletta was given a wonderful nose that continues to surprise men during wine tastings.”

But perhaps the most important thing, Giulia says, is that women are more capable of dealing with ethical issues. “In general I believe we are more ethical than men”.

Diletta says that not only women but also the new generation, male and female, are more conscious, more aware, more honest. “The new generation is able to tackle the wine business with more ethics, but there’s still a long way to go.”

5 km away, on the other side of Erbusco, I arrived at the next family owned winery, Uberti. The wine business is a relationship business, and I was thinking on the way over: who knows more about relationships better than an Italian family? It just makes sense that almost every winery in Italy is family owned. The wine business probably has the highest percentage of family owned companies in Italy, and wouldn’t surprise me if true throughout the world.

The Uberti farm dates back to 1793, and today is another women-run winery. Eleonora with her two daughters Francesca 33, and Silvia 35, talked about the importance of trust within the family as a model for success. Francesca is the administrator, and marketing and sales person and says that the roles between the sisters were naturally decided. “My sister Silvia always loved caring for animals and plants so it was obvious that she became the oenologist and the agronomist. She needs to think 4 years into the future to make a bottle of Franciacorta. She has the technical skills to do all the necessary steps, and I trust her.”

As a child, Francesca always wanted to work in the family, but at one point her mother suggested that she should find work outside the family business. “I find it absurd to force your children to do a job. Only they can decide what to do, and having a reference working in a completely different environment helps this decision,” Eleonora said. Francesca worked 3 years in administration at a pipe making factory. “It served me a lot. I learned the importance of human relationships and that everyone in the company should be involved.”

With three women at the helm, the pros and cons of working in the family multiply. “We often argue, sometimes loudly, but even that’s fun” They always seem to resolve their clashes, but every now and then “we women can be sharp tongued and stubborn and we need a male who can diffuse the moment”. This is when Agostino, the father enters with his stoic character. (He told me when I first arrived: “You’ll realize very soon that I’m not here.”) “Even our dog and our cats are all females” smiled Eleonora.

Next stop was the Ricci Curbastro winery, near Capriolo, where I met Riccardo and his son Gualberto. “Our history is responsible for our technological position today,” said Riccardo on his tour of his Agricultural and Wine Museum, which contains more than 3000 objects. “We are one of the first Italian companies to be certified for reduced carbon footprint. We produce all the energy we consume with our solar panels. Our museum here reaffirms how we got here.”

Gualberto, 25, is of the 18th generation of the Curbastri. Recently graduated from Bocconi University in Milan in economics, he is learning that storytelling is an essential part of the wine business. He appears to be keenly aware of his fathers emphasis on the the idea of balancing traditions of the past with future innovations, and especially of his father’s precision, apparent when Riccardo pointed out to his son that a 100 year-old farm tool was not in its original position in the museum, and that he should look into the matter. Riccardo has two other sons, Filippo, 21 who is studying wine making, and Daniele, 22, currently studying economics, but still hasn’t yet decided if he wants to work in the family business.

According to Gualberto, the biggest challenge for Franciacorta is communication. “In the consortium we are all pretty much aligned , but I know we can do more. The French were great at telling the story of Champagne. We are much smaller but our uniqueness sets us apart. The name Franciacorta must always come first when we talk about our wines, followed by how our land and climate expresses the freshness and unique minerality.”

At the last stop, I found Giancarlo Bozza and his son Michele under a clarifying Mediterranean sun surrounded by Amalfi plants in the garden in front of their villa. The La Montina winery is located in the northernmost part of Franciacorta as I notice the slopes of the lower alps are all around us. Giancarlo tells me about how he always used to drink the local red wine for breakfast. He spoke of the decline of wine consumption in the last 50 years, but he’s happy that today we drink less because we drink better. He urged his son Michele, 46 to study accounting since his philosophy is that he has a business that not only makes wine, but also sells wine.

At the age of 24, Michele joined the company, learning all of the production steps, but with the aim of managing the commercial and marketing side. They joke around as Giovanni cites the ongoing battle between them. “Michele comes back from Japan and says that our Brut must be even more Brut, and I say it must stay the way it is, but he always wins!”. Villa La Montina has been transformed to host over 600 people for events, weddings and tourists. “We agree instead”, says Giovanni, “that the consortium must be more active on wine tourism. Milan is an important destination for foreigners, and as Paris does with the Champagne area, Milan needs to work with Franciacorta to organize wine tourism trips as a way of introducing them to our wines.

Michele adds “yes, the best way to increase the awareness of the Franciacorta brand is to have people drink our wine. We are convinced of our excellence, so when an American tastes our Franciacorta that costs 10 euros less than a Veuve Clicquot and says wow!, we let your tastebuds do the talking. Whether that person he is here, or in a restaurant in New York, then we have acquired a new client. Slowly but surely we move forward.

We non-Italians love your language and although the names of Italian wine grapes can be especially challenging for us to pronounce, once we learn how, we can’t stop repeating them. It makes us feel sooo Italian.

Note: the original version of this article was written in the Italian language for Italian readers.

The parenthetic phrases were added here for clarification.

ut yourself in my shoes, an American who just arrived in Italy 28 years ago. Now say these three words quickly and out loud: pig. no. lo. You have just pronounced the name of the indigenous grape pignolo from the Friuli region (Italians say PEEN-NYO-LO which also means “to be fussy about something). I guess I wasn’t fussy enough (pignolo enough) to find out how to say it correctly. It’s interesting how, when pronounced correctly, it even sounds fussy.

We non-Italians are in love with your language. Dynamic, melodic, seductive and theatrical, just like the Italian people. You might say, oh, don’t stereotype us, but it’s really not so far from the truth. Italian-ness is all around us, thanks to your epic sized diaspora – there are about 250 million of you scattered around the world. We are exposed to your culture through television, movies, music, fashion, design and of course, food and wine. And for us, part of the fascination of Italian wines is learning how to pronounce their names.

The name Friuli Venezia Giulia (the most northeast of Italy’s 20 regions) alludes to its complex history and cultural intertwining, and is a challenge for us to pronounce. The land of FVG (let’s keep it simple) is also a generous contributor to Italy’s plethora of indigenous wine making grapes – Italy boasts of having the most in the world. Knowing the origins of grape names and how to pronounce them correctly gives us a meaningful and memorable connection to the place. It’s also a great way to create better awareness of these unique wines, otherwise little known on the international market, and even somewhat unknown in Italy outside the FVG region.

For us non-indigenous people to learn how to correctly pronounce pignolo, and feel it bombinate out of our mouths, gives us, even if for a fleeting instant, a satisfyingly animated sensation of “being Italian”. As the founder of 20 Mondi, a cultural storytelling project on the vast diversity of Italy’s 20 regions – 20 different worlds, I’m working on a series of whimsical videos called “Say it Like a Italian”. These brief videos illuminate the Italian-ness of wine, food and places by learning their Italian names.

The first of our video series shows the names of Italian indigenous grapes and how to phonetically pronounce them. For example, Pignolo for an American, becomes PEEN-NYO-LO. Ribolla Gialla is RE-BOL-LA-JYAH-LA. The ucelut grape is LOO-CHEY-LOOT. The thunderous sounding schioppettino is SKEE-OH-PET-TEE-NO. Tazzelenghe becomes TAHTZ-ZAY-LEN-GAY.

Many years ago I used to pronounce tazzelenghe very softly, like this: tazzy lengy. Then I discovered that in the Friulian dialect it means “tongue cutter”. Nothing soft about this grape!